The Monarchs of the North: The Kingdom of Norway's Thousand-Year Royal Journey

Step into a thousand-year saga of resilience and rebirth in the Kingdom of Norway—Part One unveils its royal past, with two more exploring the modern monarchy, royal family and Chivalric Orders!

We are proud to present an exclusive three-part series exploring the remarkable royal history and Chivalric Orders of the Kingdom of Norway. From the saga-enshrouded reign of Harald Fairhair to the defining moments of constitutional independence, this first installment traces Norway’s thousand-year royal journey up to the death of King Haakon V.

The second article will turn to the present, focusing on His Majesty King Harald V, the royal family, and the monarchy's enduring role in modern Norwegian society.

The third and final chapter will delve into the prestigious Orders of Knighthood and key national honours that continue to reflect the Kingdom’s noble traditions. We invite you to join us on this fascinating voyage through time, heritage, and the living symbols of Norwegian nationhood.

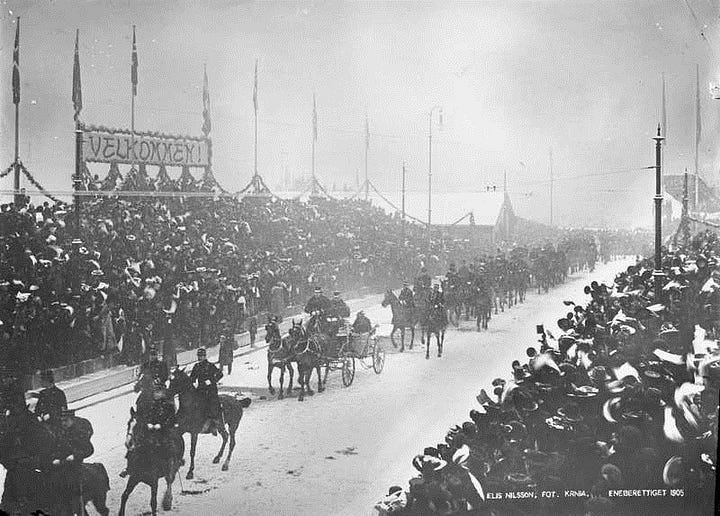

On a chilly November day in 1905, a small ship cut through the Oslofjord bearing Norway’s newly chosen king. Stepping ashore in Kristiania (now Oslo) was Prince Carl of Denmark – soon to be known as Haakon VII – with his wife, Princess Maud of Wales, and their little son, Crown Prince Olav, in his arms. The date, 25 November 1905, has since held symbolic weight in Norwegian royal history.

Thunderous cheers greeted the family. After centuries under foreign crowns, Norwegians witnessed the dawn of an independent monarchy of their own. It was a moment weighted with history: the culmination of a journey that began over a millennium earlier with the saga of Harald Fairhair, the first king to unite Norway’s ancient lands.

From the Mists of Skaldic Sagas

Norway’s royal story begins in the mists of the 9th century, an era of legendary kings and skaldic sagas. According to medieval lore, it was Harald I Fairhair (Harald Hårfagre) who first unified the myriad petty kingdoms of Norway into a single realm around the year 872. Harald, so the story goes, vowed not to cut his hair until he ruled over all Norway – earning his epithet “Fairhair” once he achieved his goal. The decisive Battle of Hafrsfjord (traditionally dated ca. 885) saw Harald triumph over rival chieftains, marking the start of a nascent Norwegian kingdom. Though later historians debate the details – some suggesting true unification came later under kings like Olav Tryggvason or St. Olav Haraldsson – Harald Fairhair stands in history as the emblematic first King of Norway.

Over the next centuries, Norway’s monarchy evolved through turbulent times. Feudal power struggles and Viking expeditions gave way to the Christianization of the kingdom by the 11th century. Saint Olav II (King 1015–1030), who died at the Battle of Stiklestad, became a national martyr and “Eternal King” in legend, cementing Christianity and inspiring unity.

By the High Middle Ages, Norway had established a hereditary monarchy and a period of relative stability under native dynasties. However, calamity struck in the 14th century: the Black Death ravaged Norway in 1349–1350, decimating the population and nobility. The weakened kingdom soon found itself drawn into dynastic unions that would deprive Norway of its monarchs for generations.

In 1380, the Norwegian King Haakon VI died, leaving his young son Olav IV (who was also heir to Denmark) to inherit the throne. When Olav IV died in 1387, his ambitious mother, Queen Margrete of Denmark, united Norway, Denmark, and later Sweden under her rule. Thus was born the Kalmar Union of 1397 – a triple monarchy with Margrete (and her successor kings) effectively ruling from Copenhagen.

Norway entered a union with Denmark that would last for over four centuries (1397–1814), during which it largely became the “junior partner.” By 1536, after a succession of non-Norwegian (mostly Danish) monarchs, Norway was even declared a formal dependency of Denmark, its royal title subsumed under the Danish Crown. No native Norwegian king would be born or reign on Norwegian soil from the late 14th century until the 20th century. Yet the idea of Norway as a kingdom endured in law and memory. Norwegian nobles and commonfolk alike preserved a latent sense of national identity through those long union years, cherishing the old sagas of their kings while foreign monarchs sat on the throne in distant Copenhagen.

Unions and the Long Road to Independence

By the early 19th century, winds of change were sweeping Europe, and Norway was poised to reclaim its nationhood. The Napoleonic Wars upended the Nordic balance of power. Denmark (allying with Napoleon) was defeated and, in the Treaty of Kiel of January 1814, was forced to cede Norway to the King of Sweden.

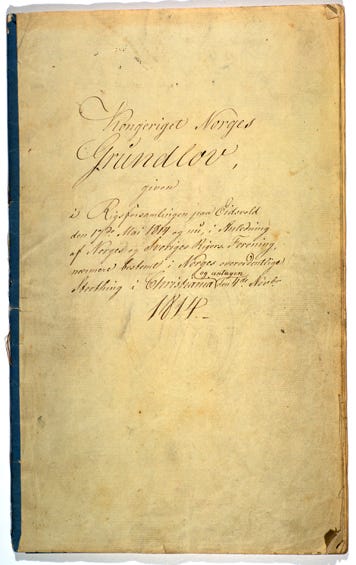

Norwegians, however, did not passively accept being transferred “like a parcel” to a new ruler. Seizing the moment, Norwegian leaders declared independence in 1814. A constitutional assembly convened at Eidsvoll in the spring of 1814, composed of about 112 men from across the country, determined to stake Norway’s claim as a sovereign nation. On 17 May 1814, they signed the Norwegian Constitution, a remarkably liberal charter for its time, and even elected the Danish prince Christian Frederik (the charismatic viceroy in Norway and a nephew of the Danish king) as the independent King of Norway.

For a brief summer, Norway tasted independence – it had its king, its laws, and the foundations of self-government. However, the great powers had other plans. Sweden, under Crown Prince Jean Bernadotte (a former French marshal who had become the heir to the Swedish throne), moved to enforce the Kiel treaty. War loomed, and by the autumn of 1814, facing superior Swedish forces, Norway opted for a compromise to avoid bloodshed. Christian Frederik agreed to relinquish his claim (later returning to Denmark, where he became King Christian VIII), and in November 1814, Norway entered into a new union with Sweden.

Crucially, this time Norway kept its hard-won constitution and a high degree of autonomy. It became a constitutional monarchy in union with Sweden – essentially an independent kingdom sharing a monarch and foreign policy with Sweden, but with its parliament (the Storting), laws, and institutions. The Swedish King Carl XIII was accepted as King of Norway (styled Karl II in Norway), and later the throne passed to the French-born Bernadotte dynasty that still ruled Sweden.

Throughout the 19th century, Norway operated in this unusual arrangement: a sovereign nation on internal matters yet bound to Sweden through a common monarch. Frictions inevitably arose as Norway’s sense of national identity grew stronger. Norwegian ministers and intellectuals chafed at Swedish dominance in foreign affairs and symbols. Nationalist sentiment flourished, fed by a revival of Norwegian language and culture, and by economic growth that made Norway increasingly confident.

By the 1890s, a particularly thorny issue came to symbolize the union’s inequity: Norway’s demand for its consular service (separate from Sweden’s) to represent its shipping and trade interests abroad. Sweden’s King Oscar II (who reigned over both countries) refused to grant this, triggering a constitutional crisis. In 1905, the Norwegian government resigned in protest when the King vetoed the Consular Service Act, and Oscar II found himself unable to form any new Norwegian government – effectively paralyzing the union’s mechanism. Seizing the moment, the Storting on 7 June 1905 passed a resolution unilaterally dissolving the union with Sweden, because the King had failed to fulfill his constitutional duties in Norway. This bold act was later overwhelmingly endorsed by the Norwegian people: a referendum in August 1905 saw an astonishing 368,208 votes in favor of dissolving the union versus only 184 against. The will of the people was unmistakable.

Sweden, recognizing the depth of Norway’s resolve, agreed to the peaceful dissolution of the union in the autumn of 1905. King Oscar II gracefully renounced his claim to the Norwegian throne. Now fully independent for the first time in centuries, Norway faced a pivotal choice: what form of government to adopt. Republican currents existed, but the Norwegian populace, perhaps recalling the stability monarchy had brought in other European nations, leaned toward retaining a crown.

In a November 1905 plebiscite, Norwegians voted decisively (nearly 3-to-1) in favor of maintaining a monarchy rather than becoming a republic. The Storting thus moved to offer the throne to a suitable royal candidate. Their choice fell on the 33-year-old Danish Prince Carl, who had impeccable royal credentials yet was known for his modest demeanor. Significantly, he was married to Britain’s Princess Maud (daughter of King Edward VII), which Norway hoped would win Britain’s support for its newly independent status.

Prince Carl, initially hesitant, agreed to accept the Norwegian crown only if the people confirmed it, underscoring that his reign would be based on Norway’s consent, not divine right. After the favorable referendum, Carl accepted the offer. In a conscious nod to Norway’s own royal heritage, he took the regnal name Haakon VII, reviving the name of medieval Norwegian kings, and gave his young son, Alexander, the name Olav as the crown prince. With that, the modern House of Glücksburg, a branch of Prince Carl’s Danish royal family, ascended the Norwegian throne.

On 25 November 1905, the new royal family arrived in Oslo amid great fanfare. Contemporary accounts describe flags waving and crowds weeping with joy as Haakon VII, Maud, and the two-year-old Crown Prince Olav stepped onto Norwegian soil as the country’s own king, queen, and prince. After five hundred years, Norway once again had its “own” monarch – a pivotal moment of national rebirth. In his accession speech, Haakon pledged to be “Alt for Norge” (“All for Norway”), a motto that would define his reign. The stage was set for the Norwegian monarchy to enter a new era as a unifying symbol of the independent nation.

HM King Haakon VII: The Resolute King and Wartime Hero

HM Haakon VII’s early reign was dedicated to strengthening the bond between the monarchy and the Norwegian people. A shy, level-headed man, he understood that as an elected king, he must earn his subjects’ trust. He learned Norwegian (having grown up speaking Danish and English) and traveled extensively across his new kingdom – from remote fishing villages in the north to industrial towns along the fjords – to introduce himself to his people. His queen, Maud, brought an air of elegance as a British princess, and their son, Olav grew up thoroughly Norwegian. Together, they helped embed the monarchy in national life, lending a sense of continuity with Norway’s ancient royal lineage even as the country charted its own course.

The true test of HM King Haakon VII’s leadership, however, came with the outbreak of World War II. In the early hours of 9 April 1940, Nazi Germany launched a sudden invasion of Norway. The royal family was hurriedly awakened and evacuated from Oslo as German forces targeted the capital to capture the King and government. What followed became perhaps the most defining chapter of Haakon’s life – one that would forever endear him to Norwegians.

The King, then 67, fled northward with the cabinet in a dramatic escape, narrowly avoiding German patrols. When the invaders demanded Norway’s surrender, Haakon faced an agonizing choice. On 10 April, in a snow-covered forest at a place called Nybergsund, the King convened an extraordinary meeting of his Cabinet. A German envoy had delivered an ultimatum: oust the elected government and appoint Nazi collaborator Vidkun Quisling as Prime Minister or face dire consequences.

Haakon regarded this demand as an assault on Norway’s democracy. With bombs falling nearby, the King addressed his government with resolve: he personally could never accept the German terms. He told them he “could not comply” with the occupier’s ultimatum and would rather abdicate than appoint Quisling as prime minister. In other words, Haakon VII was willing to give up his crown rather than betray the Norwegian Constitution and his people’s will. The cabinet, moved by the King’s stance, unanimously backed him. Norway refused to surrender outright. This moment – often called “The King’s No” – has since passed into legend. It set the tone for Norway’s resistance.

Though military defeat was inevitable, Haakon’s moral courage galvanized Norwegians. The royal family and government managed to escape to Britain, where they led a government-in-exile for five years. Throughout the occupation, Haakon VII became a rallying symbol. Many Norwegians wore badges with the “H7” monogram on their clothing (an illegal act under Nazi rule) as a quiet show of loyalty to their king and country.

On BBC radio broadcasts into occupied Norway, HM King Haakon’s speeches offered hope, his calm voice urging perseverance until liberation. And when liberation finally came in May 1945, it was Haakon – white-haired, dignified, and riding aboard a British warship – who returned to Oslo to receive the delirious welcome of a free people.

Photographs from June 7, 1945 (exactly 40 years after the dissolution of the union with Sweden) show the King and Crown Prince waving to massive crowds, with tears of joy on many faces. Haakon VII’s steadfastness during WWII transformed him from a constitutional monarch into something of a national father figure, a living symbol of Norwegian unity, freedom, and fortitude.

In the postwar years, King Haakon VII presided over Norway’s recovery and the beginning of its transformation into a modern, prosperous social democracy. Though his role was largely ceremonial, his moral authority was immense. He had tea with schoolchildren, dedicated new factories and universities, and offered words of comfort in times of hardship (such as the harsh winter of 1947 when he used his New Year’s speech to encourage ration-weary citizens).

As the 1950s progressed, Haakon’s health began to wane. In September 1957, at age 85, he passed away after 52 years on the throne – the longest reign of any Norwegian monarch up to that point. The outpouring of grief was unprecedented: hundreds of thousands lined the streets or lit candles outside the Palace in silent tribute. Norwegians knew they had lost not just a king, but the man who had embodied their nation’s spirit through its darkest and brightest days.

HM King Olav V: The People’s King

Upon Haakon’s death in 1957, his only son succeeded as HM King Olav V. If King Haakon VII was the father figure who guided Norway through war, Olav would become known as Folkekongen, the People’s King – beloved for his approachable style and genuine rapport with ordinary Norwegians.

Born in 1903, Olav had grown up with modern Norway; as a toddler, he’d been carried off the ship in 1905 when his father came to take the throne. Over the decades, as Crown Prince, Olav had prepared diligently. He served in Norway’s military (even winning an Olympic gold medal in sailing in 1928), and stood by Haakon during WWII, acting as a valuable military advisor and even Commander-in-Chief of Norwegian forces in exile. Those wartime experiences forged in Olav a profound sense of duty and solidarity with his people.

As King, Olav V maintained the monarchy’s popularity in a rapidly changing postwar society. The Norway he inherited was entering a golden age of social welfare and, by the late 1960s, reaping riches from North Sea oil. Olav understood that to remain relevant, the royals must remain relatable. He became famous for eschewing pomp and living as simply as protocol allowed. One iconic anecdote from the 1973 energy crisis perfectly encapsulates his style: during a government-mandated car-free day to save fuel, King Olav decided he too would leave his official car at home.

Dressed in a ski jumper and carrying his skis, the 70-year-old monarch hopped onto a public tram in Oslo en route to his favorite cross-country trails in the hills. A startled fellow passenger took a now-famous photograph of the King – alone except for ordinary citizens – politely paying his fare. When later asked if going out without bodyguards had been risky, Olav quipped that he had “four million bodyguards” – referring to the people of Norway themselves. Such down-to-earth gestures earned him immense affection. To Norwegians, Olav wasn’t a distant figure on a throne; he was one of them, a king who skied in the woods and mixed with his subjects unceremoniously.

HM King Olav V also upheld the constitutional role of a modern monarch to the letter. By his reign, Norwegian kings had long since abandoned any political influence – since 1884 Norway had firmly established parliamentary rule, rendering the monarch a ceremonial head of state bound by the government’s advice. Olav dutifully opened Parliament each year, signed laws, hosted state visits, and performed the symbolic functions of kingship.

But his most significant contributions were intangible: the sense of stability and continuity he provided, and the personal example he set of unity. During his reign of 34 years, Norway underwent rapid modernization, urbanization, and the rise of a more diverse society. Through all this, the kindly king with the twinkle in his eye remained a reassuring constant.

When HM King Olav V died on 17 January 1991 at the age of 87, the nation mourned deeply. An estimated 100,000 people braved the cold to line the route of his funeral procession in Oslo, while millions watched on television. In the courtyard of the Royal Palace, Norwegians placed tens of thousands of candles, notes, and flowers in a spontaneous tribute. It was said that “everyone felt they had lost a friend.” Thus, Olav V passed into history as one of Norway’s most loved monarchs.

As Norway’s royal journey enters the modern age, the story is far from over. In the next installment of our series, we turn to His Majesty King Harald V, the royal family, and the living legacy of the monarchy in 21st-century Norway. From statecraft to symbolism, tradition to transformation, we invite you to stay with us as we explore how the Crown continues to shape the heart of a nation.